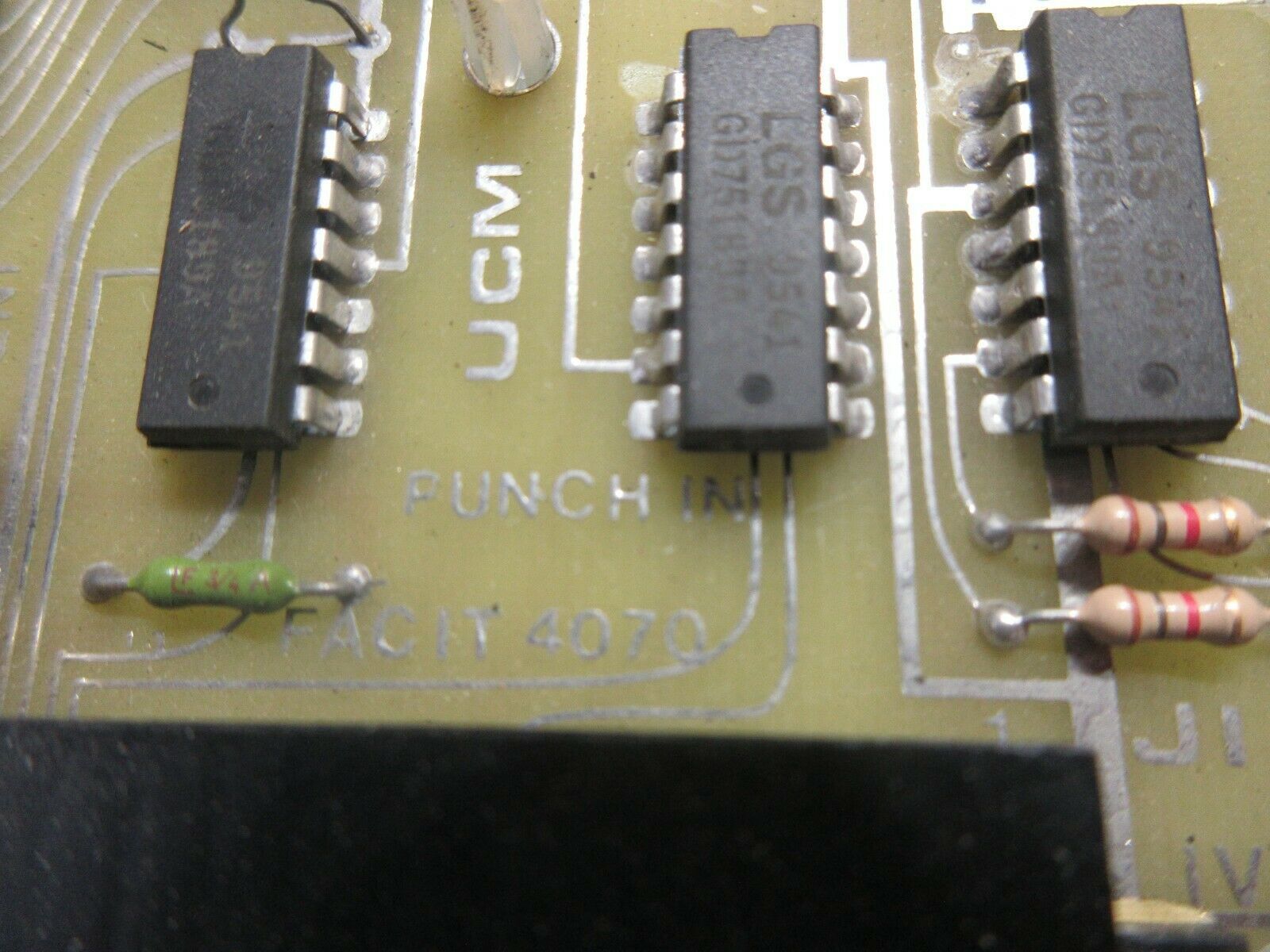

ideal, also because of its cheapness and simplicity of operation and ubiquity.” It is rationality embodied: “With only one typeface and size, with uniform inter-line and inter-word spacing and no justification, the typewriter is. The typewriter in this respect is an ambivalent machine: it empowers individual expression as much as it is a tool of corporate modernism. This democratisation of the production of printed text, along with the increased mobility of the machines which produced this text, also played a considerable role in globalisation processes which affected and were affected by business and work organisation. The new technology allowed for the relatively cheap production of printed material.” It was the democratisation of typesetting and printing. Although the assortment of styles for non-Latin fonts was rather small, the typewriter market expanded and the machines were distributed all around the world. In her article “Typewriter / Typeface: The Legacy of the Writing Machine in Type Design” María Ramos Silva writes: “Typewriter sales grew fast and manufacturers offered typefaces for different scripts. As stated in a type specimen published in the Facit Typewriting Guide from 1970 there are “a number of styles for the production of small labels, tabulations, forms, manuscripts, offset originals, overhead sheets, clear stencils, organigrams etc.” All office-related documents. We also made use of the various type catalogues which FACIT produced for its users to see the different type styles and explain the specific uses for each one. The documents which we consulted and studied were often in the form of letters most of them part of FACIT’s internal communication and some of them sent out to customers.

The design process that brought us to the typefaces used in this book emerged from stored-away-and-forgotten objects. These texts contribute to the salvation of a moment in typographic history which is often discarded and marginalised, like much of the printed material through which this history manifests itself. There are a number of essays about typewriters and their typefaces which go into more detail, and which were a source of inspiration for us during the project two examples which we would like to mention are “Type Design for Typewriters: Olivetti” by María Ramos Silva, and “Modernity, Method and Minimal Means” by Sue Walker. It doesn’t have the pretension of a general survey but stays close to our findings in the archive, to provide some context and perspective in relation to the fonts which you are seeing in this book. This text gives a brief overview of some of the things we learned. We did this in the hope of reactivating their shapes as typographic time capsules, and to put them into use again in the context of the book that you’re holding in your hands. Early on in the project we decided to develop a number of digital reconstructions of FACIT typewriter typefaces as part of our research. These were made for the user to have an overview of the alphabets stored in FACIT machines.

#Facit typewriter typeface archive#

One of the recurring documents in the FACIT AB archive are the type specimens.

Although a typewriter produces printed characters, it isn’t a machine for reproduction in the same sense as a letterpress, offset press, or photocopier - a typewriter produces unique originals. However, as much as they were ubiquitous they were also in many ways specialised and exclusive more often than not they were used for private or internal forms of communication such as letters and reports and were rarely deployed to produce text published and distributed in large editions. Typewriter typefaces were thus highly mobile, and in this sense could be compared with digital typefaces, stored on a personal computer and shared through the cloud. The machine, once purchased, was often moved from one place to another - possible due to its size and weight - and, typically, the printed matter produced on the machines was dispersed either as originals or reproduced again by way of photo-copy, stencil duplicator, or offset press. Typewriter typefaces and their imprints were circulated through the machines which carried them. Most FACIT typewriters were produced for the office space, at a desktop scale, and designed to match the industry standards of paper size and the corresponding, practical type size. Typewriter typefaces are subject to a number of restrictions which they owe to their machine-host.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)